SPT Report

As Sudan faces one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, international pressure is mounting on the warring parties the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) to accept a three-month humanitarian ceasefire. While such a truce could ease the suffering of millions displaced and cut off from food, healthcare and basic services, an agreement remains elusive. This raises a critical question: what drives the army’s persistent reluctance to endorse a ceasefire despite its mounting human cost?

Military, intelligence, political and journalistic sources who spoke to SPT point to a recurring factor in their accounts: the extensive influence of Islamist networks within Sudan’s military and security institutions. Though largely invisible to the public eye, this influence continues to shape the army’s strategic calculations.

This report brings together testimonies from multiple credible sources to uncover the layers of power wielded by Sudan’s Islamist movement inside the armed forces and security apparatus , influence that is reshaping the trajectory of the war and informing the army’s stance on any proposed humanitarian pause.

The Legacy of “Tamkeen” and Its Impact on the Army’s Structure

The roots of this influence trace back to the 30 June 1989, when the Islamic Movement through its member Omar al-Bashir, who led the coup toppled Sudan’s democratic government. From day one, the movement set out to reengineer the military on the basis of ideological loyalty, launching the most sweeping purge and restructuring in the army’s history. Thousands of professional officers were dismissed and replaced with individuals tied to the Islamist movement.

A senior member of the Association of Dismissed Armed Forces Officers told SPT that around 13,000 officers were removed after the coup, stressing that all of them were “professional officers with no ideological or partisan affiliations.”

A retired army officer who previously held a senior post in the Ministry of Defence described this “loyalty cleansing” as only the first phase. He explained:

“After getting rid of a large number of officers they deemed unreliable, they began planting their own cadres inside the army. They opened the military academy widely to Islamist recruits from universities, and they monopolised overseas military scholarships.”

He continues:

“Promotions to sensitive positions intelligence, the Republican Guard, armoured units were reserved for them. The military career path was tied to political loyalty, so an officer belonging to the Islamic Movement would advance faster. That’s how many army leaders also became leaders in the movement or its political arm, the National Congress Party. In effect, a doctrinal core was formed inside the regular army.”

He adds that this influence extended far beyond the armed forces:

“The intelligence and security service was established from the outset as an organ of the movement. That’s why all its directors since its inception have been Islamists from Nafie Ali Nafie to Salah Gosh and Mohamed Atta, up to its current director, Mufaddal. The same pattern applies to the army’s economic institutions.”

After 2019: A Dormant Network Reawakens

Despite the fall of the Islamist led regime following the December 2019 revolution, its institutional legacy remained embedded in the military and security structures. After the 25 October 2021 coup, Islamist elements regained clearer influence within the army and security services, influence that grew even stronger after the war erupted in April 2023.

Multiple assessments suggest that the war itself was ignited by calculated moves within the army and intelligence services led by Islamist actors, aiming to restore their grip on the state and block the emergence of a civilian democratic authority. As the conflict has expanded, the role of these networks has become increasingly visible, shaping the army’s decisions , including its stance toward a humanitarian ceasefire.

Former Officer: “Islamists Maintain Full Control Over the Army’s Leadership”

Retired Colonel Ali Abdel Bagi, who served more than twenty five years in the Sudanese Armed Forces, offers a direct explanation for why efforts to secure a humanitarian ceasefire have stalled. In an interview with the newspaper, he says:

“The unspoken truth is that Islamists maintain full control over the army’s leadership. The overwhelming majority of senior and mid-level commanders in the operations and command rooms either belong to them or are loyal to them. Sensitive security decisions are discussed in closed circles led by Islamists , often without the knowledge of other members of the leadership.”

Abdel Bagi argues that the acceptance of a long ceasefire is viewed within this current as a direct threat to their entrenched influence inside the military establishment:

“A ceasefire could eventually open the door to restructuring the army and returning to civilian rule. This is what Islamists fear most. If they ignited the war to bring the Islamic Movement back to power, why would they agree to halt a conflict that will not restore them to authority?”

In his assessment, the Sudanese army today operates on two distinct levels of power:

a military front that leads combat operations, and a political-security Islamist layer that shapes strategic decision-making from behind the scenes.

He adds, in unusually candid language:

“Every time Burhan appears to deny the presence of Islamists inside the army, it is a joke even Islamist officers laugh at it. Burhan is lying, and deception and dishonesty are among his traits.”

Military Expert: The War Erupted According to Calculated Islamist Planning

An independent military expert who has studied structural shifts within the Sudanese army for two decades offers an even deeper assessment of the Islamist role in the outbreak of the war. Speaking to us on condition of anonymity, he said:

“All evidence indicates that Islamists ignited the war, and they discuss this openly among themselves.”

He explains that the Islamic Movement understood that the political agreement being negotiated before the conflict would inevitably lead to military reform:

“They knew reform would mark the end of their project. For them, the war is not merely a battlefield confrontation; it is a path toward reasserting their influence.”

The expert notes that Islamists still retain extensive networks inside Sudan’s security institutions:

“They maintain full control over the leadership of the intelligence and security service, and they hold significant influence within the police. They also operate their own security apparatus known as al-Amn al-Shaabi a parallel network deeply embedded within both military and civilian state institutions. In addition, they command armed semi-military units spread across various fronts, some wearing army uniforms and others operating as shadow forces.”

He stresses that this overlap between the army and these parallel forces means that decision-making including whether to accept a humanitarian ceasefire is “constrained by an intertwined ideological and military influence.”

Inside the Army Chief’s Circle: Burhan Between Ambition and the Pressures of His Allies

A journalist with close access to the office of General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the commander of the Sudanese Armed Forces, offers another perspective on the dynamics shaping his decisions:

“Burhan can be anything. He is Islamist with the Islamists, and revolutionary with the revolutionaries. He previously worked with the Islamists as the commissioner of Nierteti in West Darfur between 2003 and 2005, when he served as coordinator of military operations there.”

The source adds that Burhan now relies heavily on the Islamists due to their entrenched military and civilian presence across the state:

“The truth is that he depends on them because of their significant influence inside state institutions. His primary objective is to become president and commander in chief of the army in the mold of Bashir. His choices are therefore political rather than ideological.”

According to the source, Burhan’s alliances are driven by survival rather than conviction:

“If the Rapid Support Forces were ever to reconcile with him and reinstate him in a position of authority, he would be willing to ally with them again. Burhan chooses the alliance that ensures his survival, not one based on a particular political belief.”

The source explains that Burhan’s hesitation over a humanitarian ceasefire stems from a difficult balancing act:

appeasing the international community on the one hand, while avoiding a rupture with the Islamists who dominate the security apparatus on the other.

But a young captain from eastern Sudan, who works in a unit with direct links to Burhan’s office, offers a sharper interpretation of the general’s motivations:

“Burhan is regional in his loyalties. It doesn’t matter whether you are Islamist or not what matters is that you are from the northern region and accept him as president of Sudan.”

Security Source: “Isolating the Islamists Will Not Come From Within the Army”

An intelligence source based in Port Sudan places the situation within a broader context, arguing that the army chief is in no position to confront Islamist influence. The source explains:

“Burhan cannot stand up to the Islamists. Their grip on the security apparatus is extremely strong, and he fears them. He does not take any step without consulting them first. If the international community wants to change the equation, it must take firm measures.”

The source proposes what he describes as a “decisive” step:

“Designating the Sudanese Islamic Movement the Sudanese branch of the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation would change the rules of the game. It would cut off their funding, limit their influence, and make any cooperation with them costly. Only then will Burhan start looking for alternative partners.”

He warns that a return of the Islamists to power through force would have far-reaching consequences:

“A violent Islamist comeback would not only threaten Sudan; it would destabilise the entire region.”

Possible Scenarios

Current indicators amid the continuation of the war and the rejection of a humanitarian ceasefire point to three potential paths for Sudan’s unfolding crisis:

First: Burhan proceeds with impossible, maximalist conditions, such as demanding the complete surrender of the Rapid Support Forces, alongside political demands aimed at undermining the efforts of the “Quad”, including insisting on the exclusion of the United Arab Emirates from the mediation framework. This comes as part of ongoing efforts he is coordinating with Saudi Arabia, through a series of communications intended to bring negotiations back to the Jeddah platform.

According to well-informed sources, the ultimate objective is to turn “Plan B,” agreed between Burhan and the Islamists, into a reality: dividing Sudan into two states one in the west (Darfur and Kordofan, excluding North Kordofan), and another encompassing the north, east, and central regions plus North Kordofan – with Burhan ruling the latter, backed by an Islamist base of support.

Second: The more likely scenario – if the international community exerts real pressure involves Burhan accepting a ceasefire under significant external influence, in a move that would push toward curbing Islamist power and removing them from key positions of authority. Should this unfold, it would represent the most realistic and beneficial outcome for Sudan, its people, and the stability of the wider region.

Third: A final scenario, still plausible if the first two fail to materialize, is the continuation of the war driven by the Islamists. This trajectory could lead to both warring parties losing control, giving rise to war-lords and extremist militias across various regions a development that threatens the fragmentation of the country and the spillover of conflict into neighboring states. This scenario remains possible given the strength of Islamist influence and their rallying cry: “It’s either us or chaos.”

Conclusion:

A Battle Over the State, Not Just a Battle Over a Truce

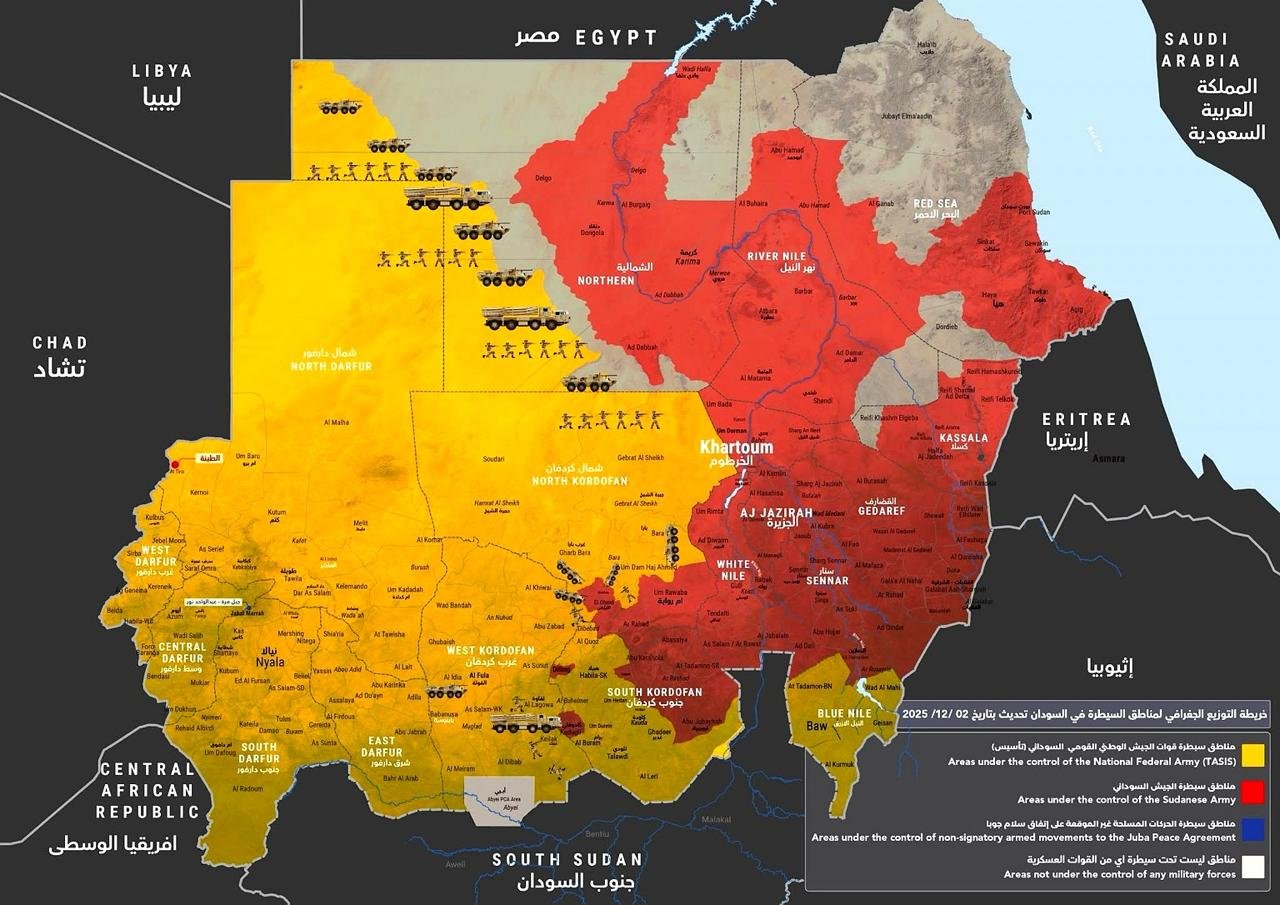

The facts on the ground , along with the testimonies we gathered, direct interviews with well-informed figures, and the military deployment maps we reviewed reveal that Sudan’s conflict runs far deeper than the visible confrontation between the army and the Rapid Support Forces. A parallel struggle is unfolding within the army’s own camp: between an Islamist power network that views the war as a pathway back to authority, a population striving to reclaim its freedom, security and stability, and an international community insufficiently engaged despite its attempts to avert total collapse.

At its core, the ceasefire is not merely a military arrangement but part of a broader contest over the nature of Sudan’s future state: who will govern it, how its institutions will function, and what trajectory the country will follow if the war continues.

A major question remains unanswered:

Can Sudan break free from the Islamist network with its dangerous regional extensions and deep hold over state institutions or will the country remain trapped in a conflict where personal military ambitions intersect with violent ideological projects?